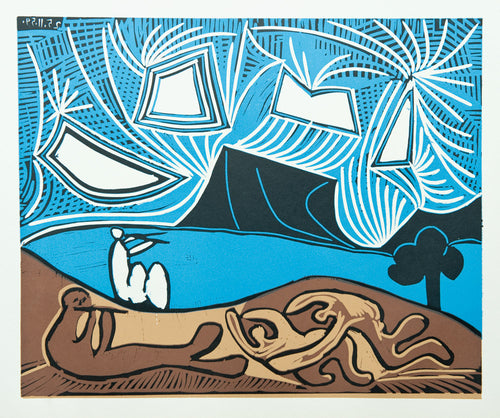

La Célestine en Action – Le Pigeon

The La Célestine suite are illustrations, or more accurately a response to one of the most significant works in Spanish literature, properly known as La Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea, a dramatized novel written by Fernando de Rojas and published in Burgos in 1499. Picasso had been familiar with the work since adolescence and in later life he collected various rare editions. The tale revolves around Celestina, an aged matchmaker whose corruption knows no bounds as she resorts to pulling one ruse after another in order to further her position.The old procuress and her hedonistic band of prostitutes, corrupt servants, clerics, officials, swaggering pimps and courtiers inhabit scene after scene driven by gross self-interest. The bawdy lewdness of the La Célestine plot is evident from its beginning, as is its account of selfish human indulgence, and the reader is the voyeur of all their sordid dealings.

Vieux Beau Saluant Très Bas une Pupille de la Célestine

Picasso had become an old man; but he was as proud as ever, he loved women as much as he ever had, and following the operation he faced the absurdity of his own relative impotence. He summed this up in a comment he famously made to Brassaï, the Hungarian-French photographer.

“Whenever I see you, my first impulse is to reach into my pocket and offer you a cigarette, even though I know very well that neither of us smokes any longer. Age has forced us to give it up, but the desire remains. It’s the same thing with making love. We don’t do it anymore but the desire for it is still with us.”

Couple et Petit Valet Encadres par une Portière

The acceptance of his own ‘castration’ was a challenge to his considerable pride; and, coupled with the isolation from the world in the villa at Mougins (a consequence of his monstrous fame), condemned him to a single-mindedness without escape. John Berger describes the aged Picasso as having a kind of mania, which took the form of a monologue. A monologue addressed to the practice of painting, and to all the dead painters of the past whom he admired or loved or was jealous of.

Une Posante sur un Piédestal

The monologue was about sex. Its mood changed from work to work, but not its subject. La Célestine, with its frank sexual content and contemplation of waning sexual potency, was the perfect vehicle for this expression. Sexual symbolism had always been one of the principle elements of Picasso’s work, and La Célestine confronted man’s and woman’s most basic impulses and passions. Picasso omits and suppresses nothing. It seems certain that late in his life he considered Rojas in much the same way that he was dialoguing with the greats of art history, transforming their work according to his own interests, turning Rojas’ Celestina into his Celestina.

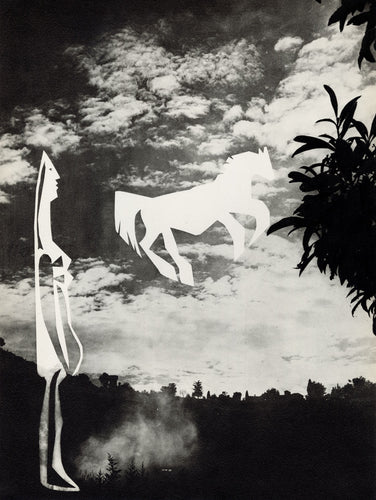

This return to a “romantic narrative” was also a reaction against the waves of conceptual and theoretical “art” that was all the rage in avant-garde circles in the late 1960s. Picasso firmly rejected the notion “anyone can be an artist, and anything can be art” and his resistance took the form of a period of Herculean creativity that pointed the way back to an aesthetic beauty, technical brilliance and the narrative of art history.

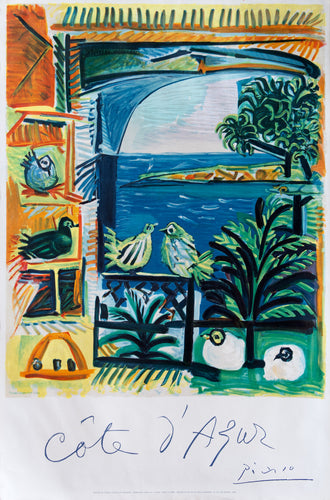

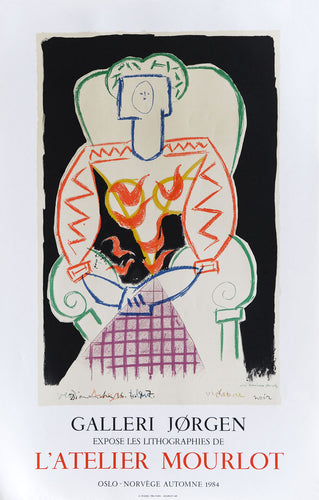

The dazzling technique displayed in La Célestine is part of this response and was facilitated by the celebrated printmakers the Crommelynck brothers, Aldo and Piero. They began their association with Picasso in 1961 at the rambling La Californie house and studio near Cannes, and when Picasso moved to Notre Dame de Vie in the Cannes countryside the Crommelyncks followed, opening Atelier Crommelynck in an old bakery in nearby Mougins.

Reitre Enlevant une Femme pour le Compte d'un Cavalier

The brothers came with a formidable reputation having worked with the likes of Braque, Miro and Giacometti. As ever, once Picasso had got his teeth into a project his aides were sucked into the vortex. The brothers devoted their entire efforts to coping with Picasso’s graphic output until his death in 1973, producing 700 engravings over this period often working through the night and proofing successive stages so Picasso could continue working on the plate the following morning. They were staggered at Picasso’s command of the technique, commenting:

“He never ceases exploring…The astounding rapidity of his hand, combined with an equal quickness of mind…enable him to accomplish in a single operation what others would be obliged to spread over several phases.”

Mille et une Nuits et Célestine La Jeune Esclave

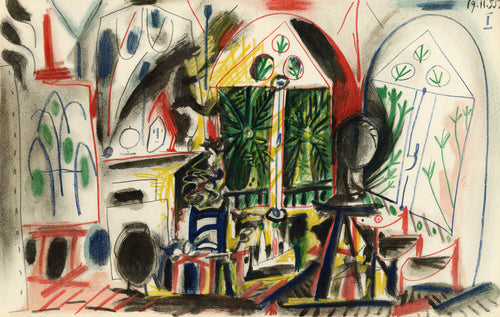

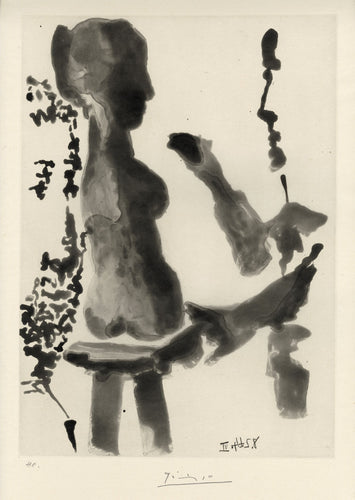

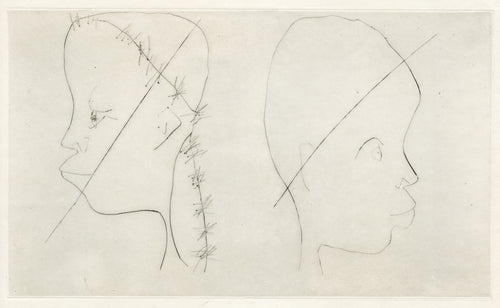

For Picasso, printmaking was an art in itself, and from1963-65 in collaboration with the Crommelyncks he refined a system of creating a whole range of whites, greys and blacks by biting his aquatints directly by hand. Working on the copper plate demanded concentration: conscious attention and the hand are absorbed by a difficult piece of work which is craftsmanlike and physical; this tense application allowed the imagination to operate more freely. Picasso manipulated the sugar lift aquatint technique by greasing the copper plate, which produced a droplet like texture which enabled him to play with light and shade without varying the strength of the black. This remarkable technique worked with extraordinary effect in plates such as Conversation and Homme à la Pipe Assis, Maja et Célestine. The skill appears to be a matter of course; one is seduced and intrigued by the balance, the rhythm and the meaning. Picasso was so in command of his craft that he only had to leave it to do its work and the details took care of themselves. The economy of means is magical.

Homme à la Pipe Assis Maja et Célestine

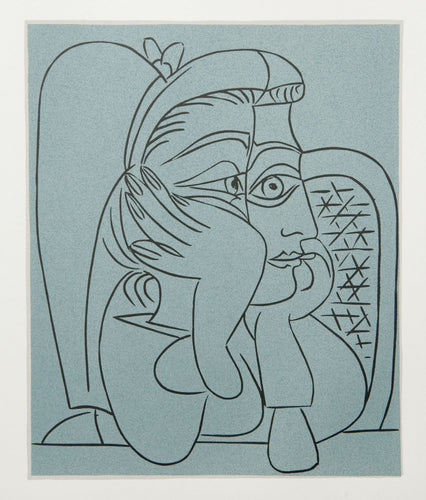

Coupled with this supreme technical skill is the highly personal and facile drawing ability of the artist’s later years. In the La Célestine etchings, the scenes are lively and articulate, the prints almost hurried in their execution, anti-modern in their crudity and seemingly as debased as their lewd subject matter. Picasso was retreating from his modernist innovations of the past. Instead of the polished Cubist compositions that were expected, viewers were confronted with what appeared to be an old man’s gratuitous scribbling of an erotic sort. However this hasty approach, as seen in Fuite à L’Aube or Enlévement, à Pied, avec la Célestine, perfectly captures the bawdy content and humour of the Célestine text and gives extraordinary life to these tiny works of art. Indeed the clever distribution of brush stroke layers in all shades between light and dark, and the enormous variety of mark making, produces a pandemonium for the senses.

Vieux faune avec une Poupée Vivante

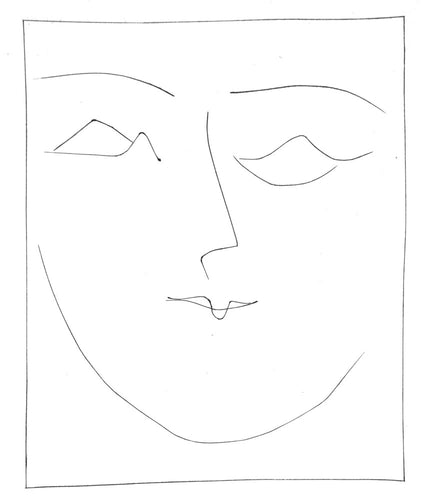

On viewing this suite in its entirety it becomes apparent that what inspired Picasso most was the lovers' meetings arranged by Celestina and held in her presence. His desire – still very much with him – now finds its gratification in the depiction of love making and amorous play and he cast himself as narrator and observer rather than the participant identifying with the aged Célestine, whose waning abilities don’t permit her to take part in the kind of sexual encounters she arranges. These later prints are about telling stories, and telling about himself. In Petit Vieux Flatté par la Célestine, Picasso’s naked self portrait depicts an old man in front of warm, fleshy, genial life, forced into the role of mere observer. The image is unabashed; he stares back at the viewer naked and resigned.

Petit Vieux Flatté par la Célestine

The suite is full of scenes of exposure and inspection, enormous nudes dominating the scene exposing themselves unashamedly and staring directly at us. Picasso delighted in their brazen attitude, capturing them at their most base and carnal, and he celebrated it. His voyeurism represented a fervent homage to life itself.

Trois Mousquetaires Saluant une Femme au Lit

Humour and parody runs through the suite; there is an intermingling of high and low life, courtly life as compared to mankind in the raw, musketeers and noblemen depicted as voyeurs or worshippers. The cavalier genuflection of the well mannered suitors entering the boudoir with the flourish of a synchronised bow, focused in on the centre of pleasure of the audacious dominating nude in Trois Mousquetaires Saluant une Femme au Lit, is both a nod to the art of the old masters and a wonderful comment on the paradox of the human condition.

Visiteur au Nez Bourbonien Chez la Célestine

Pablo Picasso was an unparalleled force of creativity who continued to invent and reinvent throughout his life pushing the boundaries of art to new extremes. It is a mark of his incredible power as an artist that this thirst for innovation never tired; he continued to paint, draw, etch and sculpt with incredible energy until the end of his life. It is their sheer bravura, honesty, wit and imagination of these ‘late works’ that makes them so fascinating and enduring. Suite 347 was a ‘succès de scandal’. Exhibited simultaneously in Paris and Chicago in 1968, it is now viewed as an outstanding artistic and technical achievement, unique in the annals of engraving.