As a central performance, and as a film that in its moral atrophy captures the failings of London’s swinging sixties, it was a triumph – but it did no wonders for the many single young women in the mould of its central character. In one now famous dance routine (to the knowingly chosen crooning tune of ‘Someone to talk to’ by the Breakaways), Christie revolves, hip-shifting, around the room, always ending up inevitably back with Harvey, her nervous hands snaking and peeling over his shoulders as they come together. At one point he lures her in, ever so slowly, for a kiss, only to softly peck at her, detach, put her back in the middle of the room. She sways around him as he drinks, her hands longingly clasped to her arms as if shivering from the cold.

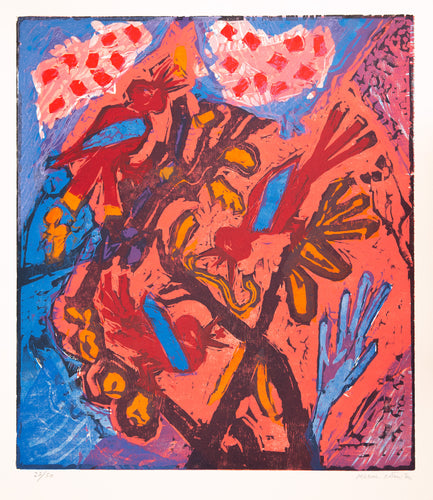

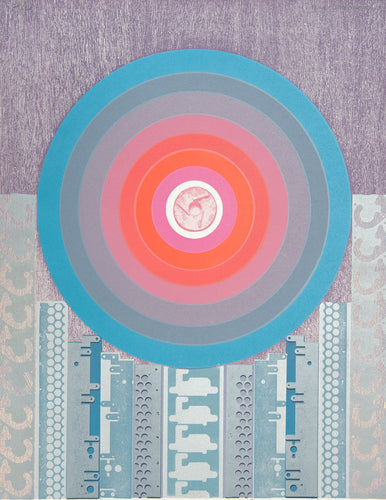

'Julie Christie', woodcut & screenprint

It’s a beautifully constructed bit of filmmaking that stands up to contrast with Michael Rothenstein’s Christie print: here too she is a bird caged, under the dominion of an ever-preyful cockerel, bound in a prison of printed wood. It is typical of Rothenstein that the particular discoveries of child and adulthood – the bright, cock-of-the-walk braggadocio of the rooster, and the ‘violent’ impress of cut timber – become the prism to this meditation on predation. It is an image that skewers the still prevalent mood surrounding the fragility of women’s careers in Hollywood, a vulnerability that was never helped by that decade’s emphasis on individual permissiveness and social laxity. By the close of the film, Christie’s ‘darling’ is left rebounding from relationship to relationship like a puck in some very sorry pinball machine, with about as much agency, pinging from apartment to club to party to palazzo.

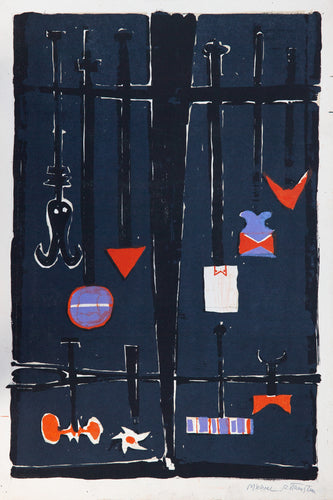

Rothenstein applies the same effect to Marilyn Monroe

If the template of Darling seemed familiar, it was only 10 years earlier that Marilyn Monroe had set the standard for young women abused by the media industry. Her career bears striking similarities to Scott’s: model turned actress, compelled to give sexual favours for a leg-up in the business, only to be exploited by sleazy producers throughout the height of her career. So closely controlled were her film contracts, that to leverage some negotiating power with executives she was forced to found her own production company, and even then failed to evolve her on-screen persona beyond free-wheeling sex symbol. When, on the morning of August 5th, 1962, her body was discovered in her Brentwood home, the papers did not take long to find their angle: ‘Marilyn Monroe Kills Self: Found Nude in Bed…Hand On Phone…Took 40 Pills’ ran the New York Daily Mirror front page. Her death was a depressing repeat of that of Jean Harlow, the original ‘Platinum Blonde’ of the 1930s, who at just 26 died from kidney failure mid-production on a film, after a gruelling schedule of six pictures in almost as many months. Monroe had been in talks to play Harlow in a new biopic before her suicide.

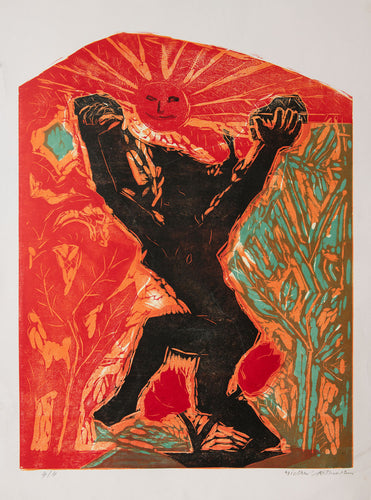

'She's American', linocut with photo-screenprint

Rothenstein had 15 years to digest this moment in media history. He had the already established iconography of Warhol, who had single-handedly made Monroe into the Mona Lisa of her age. Rothenstein’s rendition is almost a rebuttal to Warhol’s giant, technicolour head. Here Monroe barely fits her boxed frame on the page; her raised arm, meaty in the abstract, like a flexing thigh, pressed against her face and obscuring her famous hair. Below the rough expanse of dark blue and black splatter ink runs a quote from Cartier-Bresson: ‘She’s American, and it’s very clear that she is – she’s very good that way – one has to be very local to be universal.’ There is a sinister, unspoken subtext to ‘local’ here: to be universal, any man had to think he had a shot. Monroe’s ex-husband, Arthur Miller, put it rather more tragically: ‘She was a poet on a street corner trying to recite to a crowd pulling at her clothes.’

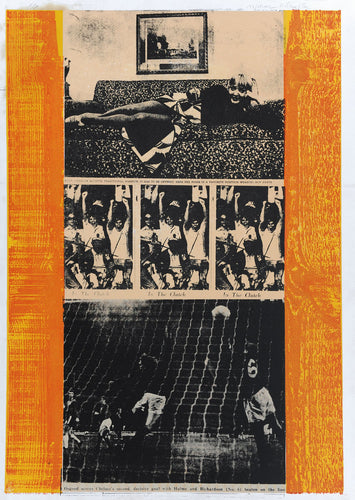

'Anna Succione', linocut with photo-screenprint; her actual surname was Fallarino

The last in this unofficially connected trio of prints cites a story that could almost be the real-life sequel to Christie’s Darling. It depicts, front and centre, Anna Fallarino (misnamed ‘Succione’), the trophy wife of husband Camillo, the Marchesi of Casati Stampa di Soncino (an old Milanese noble family). Having bought the annulment of Fallarino’s previous marriage (purportedly a billion lire deal – a warning sign, if ever there was one), Camillo, an impotent candaulist, would encourage his wife to have sex with strangers invited to their mansion. When he discovered she had struck up an affair with one such lover, beach boy Massimo Minorenti, he shot them both with a rifle before turning the gun on himself.

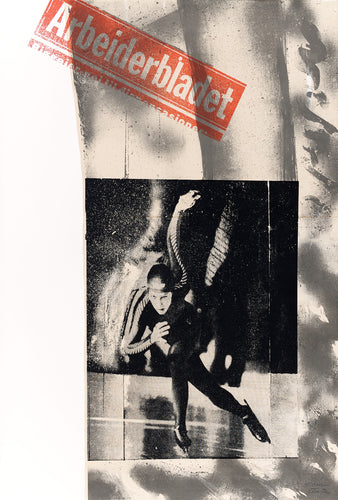

photo-screenprint poster of the Fallarino image

In a particularly morbid turn of events, the erotic photographs of his wife kept by Camillo were slipped by police to members of the media, who immediately – and shamelessly – published them in the aftermath among Italy’s crasser tabloid outlets. In Rothenstein’s version, one of these many ‘snaps’ is used. His setup, with the two repeated panels either side, mimics an altarpiece or reliquary box: and Fallarino, her crucifix slung conspicuously between her exposed nipples, is made a martyr of an age of ‘soft’ porn sensationalism and sexual violence.

As with many of Pop’s more mercurial figures, Rothenstein was remarkably prescient of the impact mass media would have on the confusion of our private spheres. ‘We lead our own life with its very definite restrictions,’ he remarked in conversation with art historian Mel Gooding, ‘with its own kind of scale, and on the other hand, we move out, through television, into this immense world without boundaries, but it's a shadow world; we move between these shadows of this inimitable space, an inimitable variety of action, people, scenes, landscapes, constantly shuffling between this immensity of the shadow world, back into the tininess of our own private world.’

Here Rothenstein was talking about one-way television; but the powerful backlash of the #MeToo movement could hardly have happened without a two-way Twitter, where private and public spheres collapse, to turn those thousands of ‘tiny’ lives and private, individual experiences into a single voice against monolithic figures like Harvey Weinstein, outing the casting couch not as a ‘droit de seigneur’ myth but an all too familiar reality. What a Rothenstein take on social media’s reshaping, and regulation, of celebrity might look like, we can never know; but from these hard-hitting, poignant prints, we can hazard a guess whose side he might be on.

The Goldmark Gallery is proud to represent the Michael Rothenstein estate.