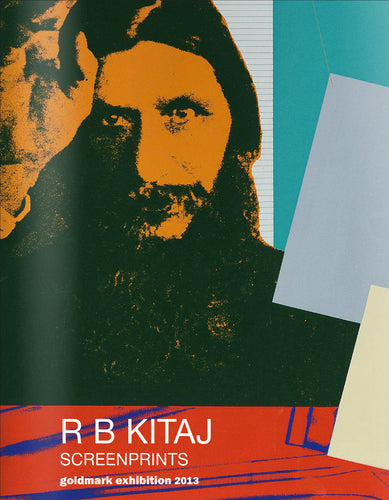

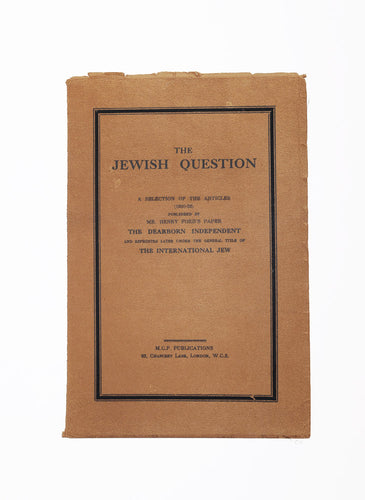

R.B. Kitaj’s A Day Book: Art, Poetry and Collaboration. Produced in conjunction with the writer Robert Creeley, ex-Black Mountain College poet and leading figure of American avant-garde literature, A Day Book arrived at a pivotal and traumatic moment in Kitaj’s life. The last major screenprint series of Kitaj’s career, before his return to figure drawing, it reveals an artist in creative crisis, propelled by events around him, and forced to confront the very nature of his obscure art.

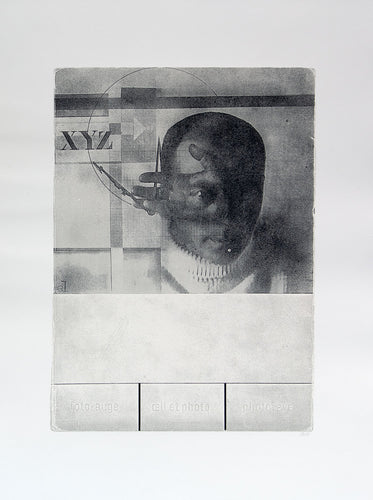

But That Was in Another Country..., screenprint & photo-etching

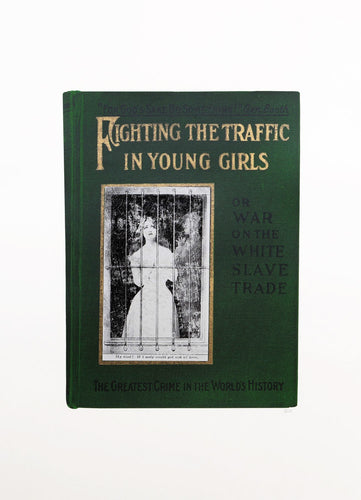

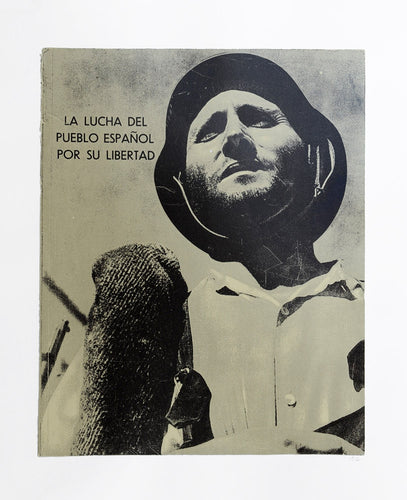

Ron Kitaj made no secret of the bookish, esoteric nature of his work. With his inaugural Marlborough Gallery exhibition in 1963 – only a year after graduating from the Royal College of Art – he made a declaration of the fact. The show was titled ‘Pictures with Commentary, Pictures without Commentary’. Whose commentary? Mostly Kitaj’s own: accompanying descriptions, explanations and general musings, sieved through a mesh of obscure and academic reference: art historians and critics (Frit Saxl, Erwin Panofsky, Aby Warburg), theorists and mystics (Walter Benhamin, Georges Sorel), poets and preachers (T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound). Verbosity became Kitaj’s habit, for which he would be denigrated throughout his career. His critics found him pretentious and ‘literary’, while to the last he remained unapologetic that his work was perplexing and his explanations for it dense and abstruse: ‘Much previous art deals with myth, histories and all kinds of ‘literary’ material,’ he declared in the wake of his first show. Whether it was Giotto or Jasper Johns, ‘you either try to find out what they are ‘about’, or you don’t bother’ – to do otherwise was intellectual laziness. A year later he doubled down on his position, with the statement: ‘SOME BOOKS HAVE PICTURES AND SOME PICTURES HAVE BOOKS’.

Allen Meeting the Visiting Professors from Toronto, screenprint on acetate

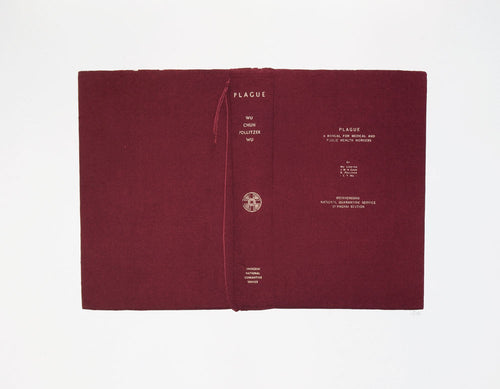

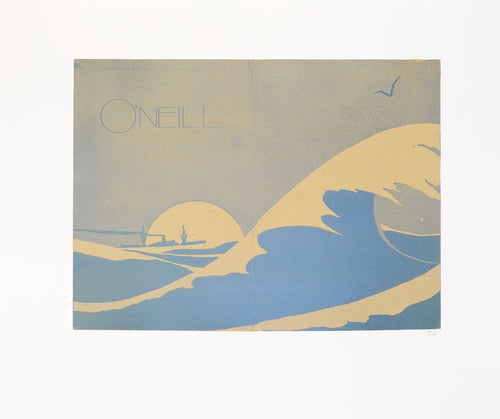

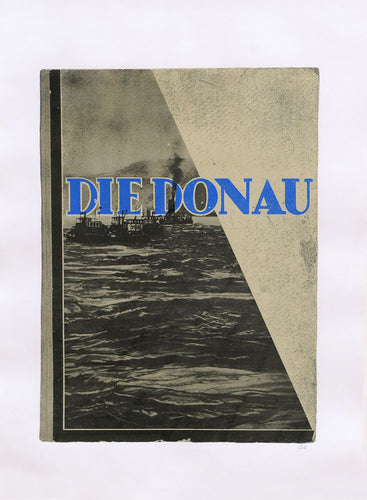

A Day Book, made in direct collaboration with the poet Robert Creeley, was perhaps the closest Kitaj ever came in print to making those words a tangible reality – closer, even, than the better known In Our Time of the same period, the library of collected book jackets he and his long-term collaborator Chris Prater at Kelpra Studios reproduced by silkscreen, where the books are pictures but no separate text attends. As with most of Kitaj’s series, in A Day Book what became a rich, eclectic and technically complex project began from a simple proposition. Kitaj had asked his fellow American for a text long enough to provoke a series of prints, and Creeley struck on the idea of a diary: ‘thirty single-spaced pages of writing in thirty similarly spaced days of living.’ Each page of prose-poetry would be printed on a different coloured paper and in a different typeface, and from the text Kitaj would pick out lines to ‘illustrate’ that had particularly struck him. Eventually the suite comprised ten prints: nine screenprints with additional etching printed by Prater, and a single lithograph, for which Kitaj’s was flown out to the Paris atelier of the Mourlot Frères.

Profile of Robert Creeley, screenprint

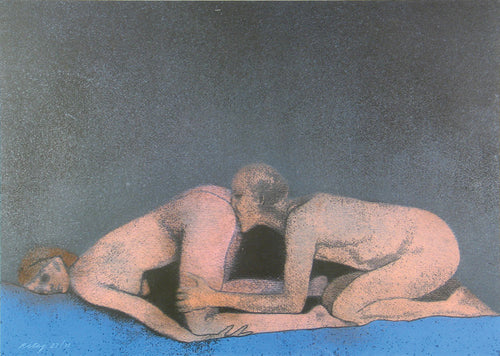

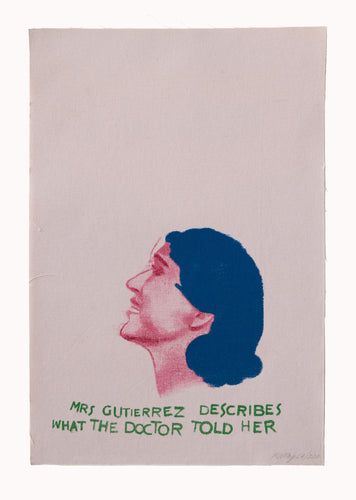

‘Without commentary’, as Kitaj put it, A Day Book reads straightforwardly as a series of portraits, drawn from his own drawings, from photographs, from artists’ prints. Faces in profile, turned away from us, staring out or to the sky in despair, they reflect the essential impetus of Creeley’s text, which was to find a sustained poetry in his daily meditations. Naturally the writer worked to his immediate surroundings: his deteriorating relationship with his second wife, the poet Bobbie Louise Hawkins; his correspondence; people, objects, drifting moods at hand, recollections of lost volumes ‘in the muddle of the book shelves back of me’. Jim Dine: Frozen and Bruised references a letter from the American artist describing an episode of transatlantic alienation which Kitaj might have felt echoed the hostility he sensed was afforded him by much of the British press: ‘I just returned from a football match, and I am frozen and bruised. My oldest son and I were thrown and crunched to the ground by a partisan crowd. These English are a queer bunch…’

Someone saying..., screenprint

Visually, texturally, the prints are dazzling – sometimes literally so, as in the sparkling blue hair of Mrs Gutierrez, printed on a Hollywood-housewife pink canvas in mock glamourisation of her suburban disarray. The catalogue of fragile, sensuously coloured Japanese papers used throughout the suite and the print techniques on display confirm that Kitaj and Prater were then at the height of their technical powers. Much of the line-work was first painted on canvas, photographed and transferred to screen, amended with hand-cut stencilling, embellished with further photo-etching, and then printed, in some instances back onto canvas. Any sense of an ‘original’ source collapses in this process of layering, printing, revising and varnishing, until, like Creeley’s text, it slips into poetic self-reference.

If one knew nothing of the portfolio besides Kitaj’s contribution, the selection of disembodied heads with lines of amended text scrawled over and in their margins might suggest the abstract realm of the inner monologue: that surreal headspace where time, colour and subject seem to dissolve and coalesce at will. But as with any other work by Kitaj, context is key. To appreciate these prints, it will help to know that A Day Book was the product – perhaps the definitive product – of a turning point in Kitaj’s career. With a traumatic episode opening the door to a new way of working, Day Book has all the hallmarks of a work made in a period of transition: a simplification of content and renewed concentration on subject, colour and tone.

Dine: Frozen and Bruised, lithograph

At every stage of his career, even his harshest critics touted Kitaj as the finest draughtsman of his generation. But he had abandoned drawing from life shortly after being introduced to Chris Prater in 1962 by the artist Eduardo Paolozzi. They soon began a close and prolific partnership, often working at distance as Kitaj travelled. Kitaj would work scattershot, treating the silkscreen and the photomechanical process that Prater was so good at as a kind of spontaneous arena where images could be thrown, almost, onto the page. He would send oils and even original collages in the post to Prater for transfer to screens (screenprinting and painting went hand in hand in this period of his career), with instructions to ‘iron them out’ if the original had caught in the roll. If any element were to come unstuck in transit, Prater was to exercise his own judgment as to where it should be affixed. Freedom and improvisation were decisively part of the process.

Of Bobby’s Shift off from Me Sexually..., screenprint & photo-etching

On the strength of this ‘mechanical’ graphic work, and on the back of his own curation of Kitaj’s work four years previous, in 1969 Maurice Tuchman, curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, invited Kitaj to take part in his now infamous ‘Art and Technology’ project, pairing contemporary artists with industry leaders (and with varying degrees of success). Kitaj was dispatched to the Burbank factory quarters of arms and aviation manufacturer Lockheed Martin to trial new methods of drawing on a computer screen – a catastrophic mismatch that reduced him to ‘utter boredom’: ‘it did and still does seem mad, in my terms, to imagine that one’s poetic references could thrive with any ease in the very thin air of Big Business.’

The timing could not have been more ludicrous. This was the height of public distaste for the Vietnam War, and Kitaj was a prominent dissenter (a year later he joined 24 other invitees in a boycott of the US Venice Biennale pavilion, withdrawing their work on the eve of its preview). Hardly the ideal moment to try and inveigle a major Pop artist into valorising the military industrial complex. Something of the oppressive idiocy of the experience is suggested in an otherwise untitled print in A Day Book. A ghostly face, familiar only from another print in the series, is hemmed in the lower righthand corner. To the left, Kitaj has reproduced an aerial photograph of a worksite; above is a violently painted wall in Francis Bacon-black and pink, crushing the composition. The whole is reminiscent of Kitaj’s recollection of the bureaucratic environment into which he had been thrown:

No Title, etching & photo-etching

‘...so much seems so funny, so ridiculous; maybe that’s got to be one of the best results: walking down endless corporate corridors each day, back and forth, miles of modern hallways, wearing a badge or two badges, carrying all kinds of important plans and papers…And the kind of fake and ultimately meaningless (for my own life) encounter over those weeks with the really enormous tidal wave of machinery and a massive technology I could never hope to approach intelligently let alone fathom. Maybe the heart of the experience lies there for me…’

After a year teaching in America, and the decisive failure of Art and Technology, Kitaj returned, half-heartedly, to England. The alienation he had experienced at the sterile heart of the machine industry began to colour his opinion of his own photomechanical work, though A Day Book would provide a more worthwhile second life for the computer drawings he made in Duncan and Inside She Was A Girl Still. His relationship with Prater slowed as his work took an inward turn. Aware that much of his graphic work was being produced and published at arm’s length, via directions sent back and forth to Prater by airmail, he began to question his involvement in such work, and the nature of collage more generally.

Duncan, screenprint

Then in September 1969 Kitaj’s wife, Elsi Roessler, died from an overdose of sleeping pills. They had met in Vienna at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, he a Jewish ex-merchant sailor, hot from the brothels of Cuba and now exploring the ‘backwaters of Mittel Europa’, she an American art student. She had joined him during his conscription in the mid-1950s and his assignment in Fontainebleau, his enrolment at the Ruskin School in Oxford on the G.I. bill, and their subsequent move to London and the Royal College of Art in 1959. She left behind her two children. He had not always been faithful, and in the company of Creeley’s equally uncomfortable disclosures in his text Kitaj found space to test his guilt: a photo of Elsi appears in the lower corner of Bobbie’s Shift Off from Me Sexually, staring plainly out from the page, cornered by a blue divide, while above a topless woman cups her bared breasts.

Elsi’s death prompted an immediate and profound period of introspection. Kitaj left England with his children, eventually settling in LA where he taught life-drawing at the University of California. Virtually ceasing painting, he renewed his focus in print, publishing the extended series In Our Time – his simplest, and perhaps most honest to date – to great acclaim. Returning to the human figure seemed almost to transport him to days under the tutelage of Percy Horton in Oxford, ‘a gentle English Cézannist who could bear down if needed on rough-hewn American ex-soldiers…from whom he could not tolerate too much neurotic art-jargon or fancy and half-formed modernity in practice.’

A Day Book was the stepping stone to this conscious return, and having long worked in assumed ‘collaboration’ with dead and exiled writers, the ‘friends I’ve never met’, he was now working shoulder to shoulder with a like-minded contemporary.

Mrs Gutierrez Describes What the Doctor Told Her, screenprint on canvas

Having known of Creeley’s work as editor of the Black Mountain Review in the 1950s, which Kitaj collected when off duty in Paris, they met for the first time in London at a literary function ten years later. Creeley’s portrait would inaugurate the ‘First Series’ of ‘Some Poets’ in 1966, marking Kitaj’s new contact with the poets of the Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Charles Olson, the college rector and a disciple of Ezra Pound’s, had drawn around him a collective of young writers working to throw over traditional forms of poetic structure in favour of a more radically free, spontaneous and improvisatory approach. Their MO, to paraphrase Pound, was to follow the music and not the metronome. Creeley’s own contribution, that ‘form is never more than an extension of content’, matched the associative and free-forming manner in which Kitaj had composed his screenprints. Perhaps as importantly, with the strong art and design influence of the college instilled by the early presence of Josef Albers, the Black Mountain poets were often practised self-publishers with an eye for format (while living in Majorca for two years Creeley had established his own ‘Divers Press’).

Kitaj ‘built a print’ out of the lines in A Day Book that took his fancy, much as Creeley had scaffolded his text according to the free-flow of his daily thoughts. Like a short story, where fleshed out lives are only sensed in the revelation of tics and behaviours, from single lines Kitaj managed to conjure whole personas: of dear Mrs Gutierrez, screaming almost, in existential dread at the sky, ‘come to get the wash yesterday, sitting at the kitchen table, describes what the doctor has told her of stroke, to wit, fat people – her own problem being overweight–don’t die, they have strokes, and then their own people don’t want to have to do with them.’

Inside She Was a Girl Still, screenprint

Creeley’s text walks, shifts, trips. Part diary, part monologue, part confession, here thought sight, sound and touch abut and stumble into one another like cars in a pileup or stragglers in a queue. In meandering, prosaic style he captures the essential clumsiness of thought, where images skip or elide with one another: ‘Fading off – mind rising, at best, much like fish used to, in bottom of pool, coming up slowly in a series of spiralling circles.’ The edges of the memories which float from text to text are often as soft and ragged as the paper they and Kitaj’s images are printed on. For a writer who collaborated with such a vast number of artists – among them William Katz, Georg Baselitz, Susan Rothenberg, Jim Dine, Elsa Dorfman, Francesco Clemente – and across such a wide range of mediums, he managed to keep that text visually strong and yet decidedly free of metaphor, symbolism, even of pictures or ‘imagery’ of any kind. But he shared with Kitaj a particularity, so that a fragment of a thought picked up or pinned down has the sense of a photographic element in Kitaj’s collages: an object humming with associations. And, like so much of Kitaj’s work, A Day Book is inescapably a project of the interior mind, the inescapable prison of one’s own interminable feelings. The estrangement that pervades the whole suite betrayed the growing disintegration of Creeley’s second marriage, but it must have provoked a deep response from Kitaj, rebounding from his own recent separation, not by acrimony but tragedy.

In his mid-70s reappraisal of his printed work, Kitaj disowned much of his early output as ‘hack’ work and ‘pot-boilers’ (though, as he admitted, they brought little money to his or Marlborough’s coffers, and had become inordinately complicated – and expensive – to print). As a transitory work, from ‘pulp’ to ‘mature’, A Day Book escaped his denigration, but it would not have been possible without the challenge Kitaj made at the outset of his career to frustrate, provoke and coax our engagement. From their mystery we move, in Creeley’s words, ‘Elsewise – a swirl somehow to things, to relationships.’